- Home

- Sheila Walsh

An Insubstantial Pageant

An Insubstantial Pageant Read online

An Insubstantial Pageant

Sheila Walsh

Copyright © 2019 The Estate of Sheila Walsh

This edition first published 2019 by Wyndham Books

(Wyndham Media Ltd)

27, Old Gloucester Street, London WC1N 3AX

First published 1986

www.wyndhambooks.com/sheila-walsh

The author has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is a work of fiction. The names, characters, organisations and events are a product of the author’s imagination and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, organisations and events is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Cover artwork images: © Period Images / Mariia Golovianko (Shutterstock)

Cover design: © Wyndham Media Ltd

Wyndham Books: Timeless bestsellers for today’s readers

Wyndham Books publishes the first ebook editions of bestselling works by some of the most popular authors of the twentieth century, including Lucilla Andrews, Ursula Bloom, Catherine Gaskin, Naomi Jacob and Sheila Walsh. Enjoy our Historical, Family Saga, Regency, Romance and Medical fiction and non-fiction.

Join our free mailing list for news, exclusives and special deals:

www.wyndhambooks.com

Also by Sheila Walsh

from Wyndham Books

The Golden Songbird

Madalena

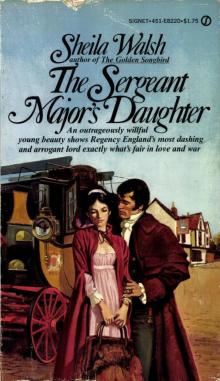

The Sergeant Major’s Daughter

A Fine Silk Purse

The Pink Parasol

The Incomparable Miss Brady

The Rose Domino

A Highly Respectable Marriage

The Runaway Bride

Cousins of a Kind

Improper Acquaintances

Many more titles coming soon

Go to www.wyndhambooks.com/sheila-walsh

for more news and information

For my lovely, long-suffering husband

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Also by Sheila Walsh

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.

The Tempest Act IV, sc. i

Prologue

The Schloss Bayersdorf stood on a rock at the head of a steep wooded gorge with its curious assortment of turrets bathed in sunshine and the formidable mountain ranges of Bohemia marching in serried ranks at its back. It looked for all the world like something out of a mythical romance. Which in a sense it was, for the tiny principality of Gellenstadt, ruled by the house of Bayersdorf from medieval times and in size no bigger than many an English country estate, was by its very situation cut off from the world. So much so that, although technically annexed by Bonaparte, it had escaped the fate of its more prestigious neighbours, being deemed of little use to anyone ‒ its only claim to singularity being the exquisite silverware for which it was famed.

It was hot that afternoon and the long windows of the throne room were flung open in an effort to trap whatever fresh air might be found. But the fine muslin curtains scarcely moved, and for Grand Prince Adolphus each breath was a small agony …

He stood with his back to the room, the set of his shoulders proclaiming a man of stern disciplines ‒ an impression confirmed by the rigid conformity of his dress which allowed of no concession to the heat. It was therefore some considerable measure of his discomfort that one hand occasionally moved unobtrusively to tug at the high tight collar of his coat as though in a vain attempt to ease his breathing.

The furtive movement did not escape the notice of the young lady occupying the ornamental sofa nearby. Baroness Lottie Raimund contemplated that tortured yet still handsome profile with veiled concern, noting how cruelly the light slanting across it emphasized the mask of hauteur which so effectively kept people at a distance (though it had never done so with her); it emphasized too the Prince’s growing frailty, the ravages wrought by pain, which a trim, greying beard imperfectly concealed.

But she permitted no hint of her disquiet to cloud the smiling eyes lifted to him in candid speculation as he turned at last to speak.

The Grand Prince allowed himself the luxury of dwelling for a brief moment on their warmth.

They were lovely eyes, he mused, irresistibly moved as always by the perpetual evocation of spring in their purple-blue depths ‒ a kind of rich velvety texture which mirrored almost exactly the vivid gentians that carpeted the slopes above the Schloss each year in early March, and which he doubted he would live to see again. The realization, catching him for once off-guard, threatened his hard-won acceptance. Ah, why was it always the small things that got beneath one’s skin? He almost groaned the words aloud.

But the moment of weakness was ruthlessly quashed, the only evidence of its passing an involuntary tightening of the mouth which might as easily be attributed to a spasm of physical pain.

‘Forgive me, Charlotte,’ he began with the old-fashioned formality of address that had always made it difficult for him to accept the more familiar diminutive of her name. ‘You must be wondering why I have sent for you?’

Lottie knew perfectly well what, or more accurately who, had prompted the interview, but she had wisdom enough not to say so, preferring rather to try if she could to tease him out of his obvious preoccupation with pain.

‘Indeed, sire. I have spent the whole of my journey here in a quake, racking my brains for evidence of recent misdemeanours!’

She was granted the satisfaction of drawing from him a faint abstracted smile as he continued: ‘This Peace Congress they are to hold in Vienna shortly ‒ my mother tells me you have a mind to attend it?’

Lottie swallowed the retort which sprang impetuously to her lips, choosing her words with care, speaking lightly.

‘I fear that Her Serene Highness does not approve my decision. She feels that young ladies, even widows of unimpeachable virtue ‒’ she almost added the damning ‘English-born’, but thought better of it ‘‒ should not, in Her Serene Highness’s judgement, go unprotected into such fast company as will most certainly be gathered there.’ Her expressive eyes invited him to enjoy with her the comic absurdity of such a view, and when he did not immediately do so, she said with determined good humour, ‘Do you mean to censure me also?’

‘My dear Charlotte,’ he said with considerably less constraint, ‘it is not for me to approve or disapprove. You must know that you are at perfect liberty to go wherever you please without applying to me for permission.’

‘Why, so I had supposed.’ She hesitated, aware that he had stopped short of saying more. ‘Yet you do not quite like the idea of my going, I thi

nk?’

‘Would you heed me if I said that I did not?’ he asked dryly.

A rueful smile curved Lottie’s mouth. ‘I would not care to incur your displeasure.’

‘An equivocal reply, my dear … eminently worthy of a diplomat’s daughter.’ But an answering smile softened the severity of his features, robbing the words of much of their irony. ‘However, I repeat it is not for me to presume to censure you. I haven’t the right, and in any case there will be many people coming out from England to attend the Congress and it would be quite wrong in me to deny you the opportunity of meeting them and perhaps renewing old acquaintances.’ His shoulders lifted in a gesture of resignation. ‘It is more than two years since your husband died. I am only too aware that there is little to hold you here now.’

‘But I love Gellenstadt! It has been my home for the last eight years … the only settled home I can remember!’ Lottie rose, the soft peach-bloom silk of her skirts billowing as she moved swiftly across the room, her hands extended in a gesture of supplication. ‘It is only a visit I intend, truly.’

‘Yes, of course.’ The Prince took the hands she held out to him, feeling as always the curious sensation of strength that seemed to flow into him from her warm yielding clasp. He tried not to think how he would continue to exist while she was away, without the constant encouragement her presence gave to him.

‘Eight years is a long time,’ he said slowly.

‘A lifetime,’ she agreed. ‘I frequently ponder upon how different my life might have been if poor dear Otto had not so gallantly offered me the protection of his name when Papa died in that tragic accident. I can still remember quite vividly how I felt ‒ trying so hard to be sensible ‒ willing myself not to give way to that terrible feeling of panic as I faced the prospect of being entirely alone in the world, for we had nothing in the way of close family, you know.’

A convulsive tightening of his fingers caused her to look him straight in the eyes. What she saw there would have daunted anyone else, but she continued doggedly. ‘But you did know, didn’t you? Somehow you guessed exactly how I felt. I have never voiced the thought until now, but whenever I do dwell upon my good fortune it becomes more and more obvious that Otto, good sweet man though he was, would never have dreamed of offering for me, had he not been prompted to do so … from a higher authority, perhaps?’

The Prince pursed his lips, his hauteur now very evident. ‘You have a fertile imagination, my dear. Otto was devoted to you.’

Lottie chuckled. ‘Ah, now it is you who are being equivocal, sire. But I won’t press the matter. In truth, I have been more than contented with my lot.’

He released her hands, relieved that he was not obliged to dissemble further. He might, under pressure, have found it exceedingly difficult to convince her that his then Secretary of State, though the most amiable of men, had not taken a certain amount of persuading before he could be brought to relinquish his comfortable bachelor existence at a relatively advanced age in order to secure Charlotte’s future.

He had convinced himself at the time that he must accept responsibility for Sir Charles Weston’s untimely death, which had happened on a hunting trip arranged for his pleasure while he was engaged in a diplomatic visit to Gellenstadt in that winter of 1805 … and, likewise, for the seventeen year old Charlotte who had been so sadly orphaned. But if he was honest he had been captivated by Charlotte from the start, and could not bear the thought of her returning to England, perhaps for good.

How different his own life might have been had he then found the courage to defy the outraged sensibilities of his mother and the disapproval of those closest to him in order to marry Charlotte himself. But the reserve in his own nature ‒ a curse from childhood ‒ and his strong sense of what he owed to his position had held him silent. And Charlotte had married Otto Raimund.

‘I can still remember the first time I saw you,’ he said involuntarily. ‘Jungfer Husch, I called you ‒ our “miss in a hurry”!’

‘Oh, yes!’ This time her laugh spilled out, echoing round the throne room with a flagrant disregard for its vaulted splendour, flirting among the ancient tapestries like a much-needed breath of fresh air. ‘Such a great lump of a girl I was then ‒ all arms and legs and awkwardness ‒ always wanting to ride everywhere ventre-à-terre! Papa must have despaired of me many a time!’

‘On the contrary, Sir Charles was quite inordinately proud of you. It was evident whenever he spoke of you. He told me once that you warmed his spirit …’

‘Papa said that?’ she asked softly.

Prince Adolphus inclined his head. ‘And I know exactly what he meant, for I too was aware of that quality in you from the very first. You are the only person I think, who never once stood in awe of me.’ His mouth quirked in a self-deprecating way. ‘That may not seem of importance to you, but for me in those early days it was a revelation. There was then ‒ and still is in you a great openness of character ‒ a capacity to interest yourself quite genuinely in other people to a degree that transcends mere curiosity ‒’

‘Please!’ she begged in blushing confusion. But it was a long speech for so shy a man, and she would not offend him for the world. ‘Indeed, it is more than kind of you to account as a virtue what most people might regard as interference … and to not so much as hint at my unbiddable temper which still occasionally leads me to say more than I ought!’

‘Oh, that!’ He dismissed it. ‘A show of spirit is no bad thing once in a while ‒’ he smiled faintly ‘‒ and you are always full of remorse afterwards.’

As she stood quiescent, with the laughter still lingering in her eyes, it was difficult for him to equate the slender elegant creature in her stylish high-waisted dress with that merry madcap of old. She was a little on the tall side for a woman, confident and graceful in her movements, the girlish plumpness long gone. Marriage to Otto, himself a man of great style, had done much for her. But there were still glimpses of that other Charlotte in the vivid mobile features ‒ in her generous mouth with its full, deliciously curvaceous lower lip. And in her rich red hair, the luxuriant tumble of curls having long since given place to a fashionable fringe, and in her eyes ‒ something she was probably quite unaware of ‒ a curious innocence that belied all the rest.

The Prince sighed. ‘I could wish that my Sophia had a little of your strength of character.’

Lottie felt a spurt of indignation as she thought of the grave young girl, on the brink of beauty, but shy like her father, with any tendencies to forwardness swiftly repressed by a too-strict governess, at the instigation no doubt of her grandmother.

‘Oh, how unjust!’ she exclaimed. ‘Your daughter doesn’t want for character. I admit that she is something of an air-dreamer at present, but I daresay that comes of being rather too sheltered from life.’ She longed to say more, but now was not the time. She contented herself with saying warmly, ‘Sophia is in many ways a very young seventeen, but she has a lot of good qualities.’

‘She also has a stalwart champion in you, my dear,’ he said dryly. He smiled briefly and turned back to the window once more. ‘In point of fact, it is of Sophia that I really wished to speak. I’m sure that you are right when you say that she has been overprotected ‒ losing her mother so early in her life ‒ my own mother’s influence …’

His shoulders stiffened perceptibly, though whether from pain or merely painful memory Lottie couldn’t be sure. When he presently continued his voice was firm.

‘But all that must now change. A husband will have to be found for her.’

Lottie stared. ‘My dear sir, you cannot mean to catapult the child straight from the schoolroom into marriage. It would be too cruel.’

‘She is the same age as you were when ‒’

‘My case was different! Oh, surely there is plenty of time for Sophia?’

There was a small silence. Then: ‘For Sophia, perhaps,’ he said quietly.

Fear jolted her, tightening its grip on her stomach. She moved forwar

d to lay an urgent hand on his arm.

‘Your health is not worse?’

‘No worse than usual.’

‘Then how dare you frighten me so?’ she cried.

He turned his head. His eyes sought hers and found them bright, with chips of anger masking a greater fear.

‘It would be absurd, however, to assume that time is on my side,’ he said steadily. ‘There are, besides, so many uncertainties here …’ He stopped abruptly and covered her hand with his. ‘Come, I am only seeking to ensure that my daughter will be safe, should anything happen to me. That is surely the very least that a father can do?’

‘And happy, too. Sophia must be happy as well as safe!’

‘Yes, of course.’ His voice betrayed a hint of irritability, as though he were tiring fast. ‘I am not insensitive, I hope. The matter I wished to broach ‒ and it seems to be taking an unconscionable time to come to the purpose of our talk ‒ is, whether you think the Congress would make a suitable venue for Sophia to make her curtsy to the world?’

He had succeeded in surprising her. ‘It would be ideal,’ she said. ‘After all, where else could one hope to find so many of Europe’s finest families gathered together?’

‘That is what I thought,’ he mused.

‘So you have decided to come to Vienna, too, sire. I couldn’t be more pleased!’

The Prince held up a hand. ‘No, I had hoped, but it will not now be possible.’

He made no attempt to enlarge upon his reasons, but it would not be difficult to hazard a guess, Lottie felt. Quite apart from his precarious state of health, there had been one or two instances of unrest in Gellenstadt recently which, though not serious of themselves, might well make him reluctant to be away. But if the Prince did not wish to undertake his daughter’s coming out in person … Something in the way he was looking at her caused Lottie’s eyes to widen in sudden realization.

‘You would entrust Sophia to my charge?’

‘I can think of no one better suited, though I am aware that it is asking a great deal of you.’ He silenced the denial that rose spontaneously to her lips, unable quite to hide the bleakness in his voice. ‘It is a sobering reflection that you probably understand my daughter better than I do ‒ better than any of us do, in fact. However, I appreciate that such an arrangement might place unacceptable restrictions upon your freedom. You will need time to consider …’

The Golden Songbird

The Golden Songbird A Highly Respectable Marriage

A Highly Respectable Marriage Cousins of a Kind

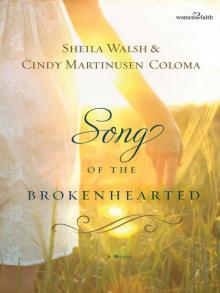

Cousins of a Kind Angel Song

Angel Song Madalena

Madalena The Sergeant Major's Daughter

The Sergeant Major's Daughter Song of the Brokenhearted

Song of the Brokenhearted